I don’t think either when instead of jumping on, the kid grabs my bag: I just jump off after him. The doors catch my shoulder as they close, and I hop along as best I can as the train accelerates. With a final pull I’m free, but I’m spinning round, and trying to run as fast as I can backwards to stop myself falling over. For the briefest moment there’s an illusion of control, and then my feet go over the end of the platform and I’m pedalling like a cartoon character as I plummet the five feet or so to the tarmac. I’m not thinking when I roll away from the vast metal wheels that grind past my elbow. I’m not thinking when I jump up and run back into the station – adrenalin is a hell of a thing – pushing screaming bystanders out of the way, gradually becoming aware I’m only wearing one shoe, and that the fact everything’s blurry means I’ve lost my glasses. The boys are gone. My bag is gone. My camera, all my photographic equipment, my brand new kindle, it’s all gone. It’s all gone.

My plane was delayed leaving Gatwick. I didn’t mind – it meant I flew over the Alps at sunset, the light just catching the snow-clad resorts I’d skied in my youth: peach crests on deep blue waves, heavy black outlines of tree and stone. It did mean I got into Tunis a bit later than I expected, and by the time I made it into town it was about half seven. All the Arabic cities I’d been to before ran late into the night, fuelled by caffeine and dominoes, so I was a bit surprised to find the main street, avenue Habib Bourguiba, almost deserted. Razor wire spiralled round several buildings and out onto the pavement, forcing you to cross the road under the watchful eyes of army recruits. The temperature was mild, and there was the slightest breath of mist, which ghosted the headlights of the slow flow of taxis that didn’t seem to be taking anyone anywhere.

If anything, it got quieter in the streets around my hotel, hard up against the medina. Cats mewed and scratched through piles of rubbish, everything was shut, and I started to feel like I’d stepped into some post-apocalyptic movie (there Needs to be an Arabic zombie movie). At least the hotel was open, nicely tiled and relatively friendly. I was a little concerned about heading back out, but I needed to eat. I also wanted to try and figure out the city I would be staying in for the next ten days, covering the anniversary of the revolution and shooting a documentary on how things had changed. The maze of the medina with its warren of ancient streets could wait. I was sure that unless things had radically changed since the revolution, I should be able to find somewhere to eat in the centre of a city of two million people at eight o’clock at night.

I didn’t have to walk too far in the backstreets below Habib Bourguiba to find the ‘nightlife’ zone. The bars were buzzing. Again, this was totally different from what I was used to. Bars in Arabic cities are normally sad places with a scattering of crying, moustachioed men, waving their arms and declaiming the ways the world has hurt them. The moustaches were still present, wrapped around bottle tops or cigarettes, but here they were resting atop smiles and garrulous chatter. The bars were absolutely rammed – I doubted a Sunday night back home would compete in terms of punters – and the thought of squeezing in for a drink wasn’t massively appealing. Still, where drunk people congregate, greasy food must follow, and I soon found a friendly restaurant where ordering a quarter chicken got me salad, beans in sauce, chips and a baguette on the side. I was tired and couldn’t face arguing, but I expected to be stung when the bill came. It was delicious, and it turned out all the sides were included in the price, a princely one pound fifty.

Walking back home I was surprised to hear through a wall what sounded like Arabic karaoke over Spastik. If I hadn’t been tired – nothing is as wearying as sitting very still for most of the day whilst being transported over a quarter of the world – then I would have investigated further. I made a mental note to investigate at the next possible opportunity, but despite my best efforts this joyous sound has never been repeated.

I was approached by my first panhandler on the way home. I have since found out they haunt Habib Bourguiba at all times, preying on Western flesh, and you start to get a sixth sense for them that allows you to change direction a couple of times and shake them off. Theoretically, these guys are easy sources, so I tried to probe this one for information. His name was Omar, and aside from flattery (it was clear to him I was a man of culture, a man of the world) he was very happy to talk about this ‘révolution des conneries’ – perhaps best translated as a revolution of idiocy, given the unpalatability of the direct translation. Things were moving too slowly for Omar, where were the jobs, and specifically, how come the government hadn’t given Omar a job? He suggested that we go and get a beer to discuss this terrible injustice further, his scent suggesting this wouldn’t be the first he’d had that day. When I declined, he recommended that we head straight into the medina. What better way to spend your first night in a new country than with a drunk in a deserted labyrinth?

One better way, of many, was to shake him off, go back to the hotel, get some sleep, and be ready for the next day, when things would hopefully make a bit more sense.

The medina at night

The medina at night Only the occasional moped braves the narrow alleys of the medina. Apart from a couple of streets, the souks here are aimed more at local needs than at those of tourists. Perhaps for this reason, there’s very little hassle. The only time I noticed any was when a Russian tour group was in town, when the transformation was remarkable. Suddenly everyone wanted to be my friend, no matter what their shop sold, and I was awash with offers of tea. As medinas go, it’s big, and although lacking some of the spectacular architecture of cities such as Cairo or Marrakech, its winding streets have a definite charm. Here and there they lean together to create domed thoroughfares conflating the concepts of inside and outside, but even in places where it doesn’t there’s barely a sliver of sky that makes it down to the torrents of humanity that wash its streets. The old city was built around a hill for defensive reasons, and this three dimensionality makes it feel like its own world. Coupled with the lack of any skyline, it starts to feel all encompassing, almost womb-like. I wonder how often people left when the city used to finish at the walls?

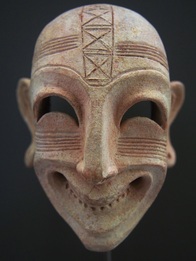

Awesome Carthaginian sculpture at the Bardo.

Awesome Carthaginian sculpture at the Bardo. Not that there was a lack of this available around Tunis as well. A palace in the medina was putting on a show of new artists, which I thought would be ideal for taking the pulse of the nation. What was going through the minds of the young generation? Mostly, it was breasts. A totally abstract cross between Pollock and Rothko, with a hint of Gerhart Richter and a big naked woman in the middle. A scribble of women and more women drawn all over the top of each other, their breasts gradually getting bigger. A nice abstract carpet, sans bosom.

The last bokeh you're seeing this trip...

The last bokeh you're seeing this trip... Not long after I visited the Salafis came and burnt down the tomb of poor old Bou Saïd – Sidi means saint, and the Salafis were apparently making a point about saint worship, much as the rebels in Mali had pulled down the tombs in Timbuktu. The difference is that there’s no real tradition of saint worship in Northern Tunisia. Burning down a harmless saint’s tomb in one of Tunisia’s prime tourist spots two days before the anniversary of the revolution, when the eyes of the world would, however briefly, be focused on Tunisia, shows that once again Islamists have had either a clear grasp of symbolism or a killer PR department. Rather than pre-modern, Islamism often turns out to be a post-modern movement par excellance.

The anniversary of the revolution itself went past without much drama. On the Sunday the day before there was live music on Habib Bourguiba. Mostly it was traditional music, with the Hip Hop that had soundtracked much of the Revolution itself mostly confined to big screens between the stages. I should, at this point, mention that most Tunisian Hip Hop I’ve heard is fairly awful. I’m sure the lyrics are great, but the production is understandably terrible, autotune casts its baleful influence, and the flows are really weak. It sounds like a limper version of Road Rap, with Arabic instruments.

The vast majority of people over the two days were just wandering around, munching popcorn, taking it all in and enjoying the holiday. There were a lot of Tunisian flags. Everyone seemed to have forgotten about their worries and agreed that the revolution was a wonderful thing. I bumped into Omar, who was drunk, and as he kissed me on both cheeks he told me how glorious the revolution was and how great things were.

There was a hardcore of marchers, though. On the Sunday night a little under a thousand of them marched up and down Habib Bourguiba chanting slogans, holding aloft pictures of people they had lost, and a mock martyrs coffin covered in blood. For the most part the crowds not taking part looked on bemused, but everyone cheered when someone let off a flare, and the one slogan that everyone joined in on was ‘Ash-sha’ab yurid isqat al-nizam.’

Without going deeply into the etymology of the words, suffice to say that a better translation could be ‘the people want to bring down the system.’ On the Monday of the anniversary itself, along with all the thousands of Tunisian flags (and a handful of the black Salafi ones), there were a large number of other Arab states’ flags – with the Palestinian flag being the largest one, but with representation for Egypt, Syria, Libya and so on. The system that Tunisians want to break down isn’t restricted to the regime that terrorised them and stole their money. Tunisians feel their place within the world, they’re proud of what their country has started and how it has spread, and they want to see the current world order shaken up and a fairer deal for all. If they’re as susceptible to conspiracy theories as Egyptians then they’re too polite to mention it to me, but it’s fair to say that they regard the international system that supported the status quo in Arab dictatorships – and still does in places such as Palestine and Bahrain – as not entirely favourable to the world.

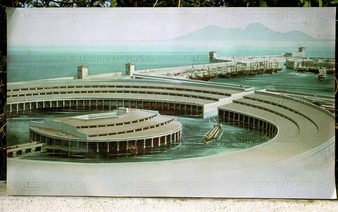

Carthage was an interesting mix of a posh, almost Americanised suburb, laced with ancient sites. There was a harbour with a central island that had originally held lots of warships up ramps, ready to launch Thunderbird like. Above this rose the hill that Carthage had originally been built on, with many of its old streets well preserved as the Romans had filled them in to build a temple complex on top. When the French came they promptly built a cathedral on the symbolic site, and the President’s palace is currently just down the road.

Carthage eventually became the third largest city in the Roman Empire, a fact well attested to by the size of the Roman baths that remain. This complex is so vast that what archaeologists initially thought was a theatre ended up just being some communal toilets. There’s an 18 metre high column still in place that weighs eight tonnes, together with its missing partners it would have held up the roof of the frigidarium and created a space that many cathedrals would be jealous of. All this majesty was right next to the sea, and I considered hanging out for a cup of tea whilst the sun set, but decided to head down to La Goulette, or ‘the gullet’, the port of Tunis famous for its fish restaurants and nightlife. It was so easy to get around thanks to the TGM suburban train…

Standing in the road, gazing round blurredly, it took me a while to see it had really happened, that everything was really gone. Someone hands me my shoe, another person passes me a twisted scrap of metal with vague memories of being my glasses. I start to be able to express myself in French, instead of just screaming “Where are the boys?” and everyone tuts and looks disappointed. The thieves have long gone.

A friendly old man decides to drive me to the police station. Getting the keys from his TV shop, he jumps in the car, leaving the shop open with no-one watching it. He doesn't worry that anything will be stolen from it as theft is so rare in Arabic cities. The police take my statement and generally all gather around and frown. I’m driven from station to station to look at mug shots on decrepit computers, the adrenalin wearing off and my body starting to complain that bouncing it off tarmac at high speed isn’t one of its preferred activities.

Disturbingly, the older the pictures, the more evidence there is of beatings. Faces are bloody, covered in tears and terror. Eyes are swollen, blood drips from noses and mouths. All the suspects look poor and desperate. None of them look like the kids who robbed me.

The chief investigator arrives, gets out his phone, far more powerful than any of the computers at the police stations. Here the photos are different. Kids in expensive clothes, caps balancing on top of coiffed hair, chins stuck out defiantly. These recent photos have swagger, there isn’t any fear here. I think I recognise one of them, but I’ve been looking at photos for so long there’s a high chance someone just looks familiar from another photo, the faces starting to blend into one and eliding the faces I glimpsed just for seconds on the train.

As I’m once more driven fruitlessly between stations, the police chat in Arabic, and I haven’t yet been able to get to grips with the Tunisian dialect. A guy who doesn’t seem quite to fit with the rest of the officers, who a million cop shows have convinced me lies somewhere between assorted toady and informant, says in French “C’est une révolution des voleurs” – a revolution of thieves. Giggling slightly, he repeats it again and again, glancing sidelong at me to see if I’ve understood. The rest of the cops look stoney faced and eventually hush him. I look out the window at the country I don’t yet understand, and just wish it was all over and done with.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed